Column Vol. 3 “Walls Don’t ‘Trap’ Moisture, They ‘Manage’ It — PAVATEX, The Breathing Insulation”

Ono from Wald

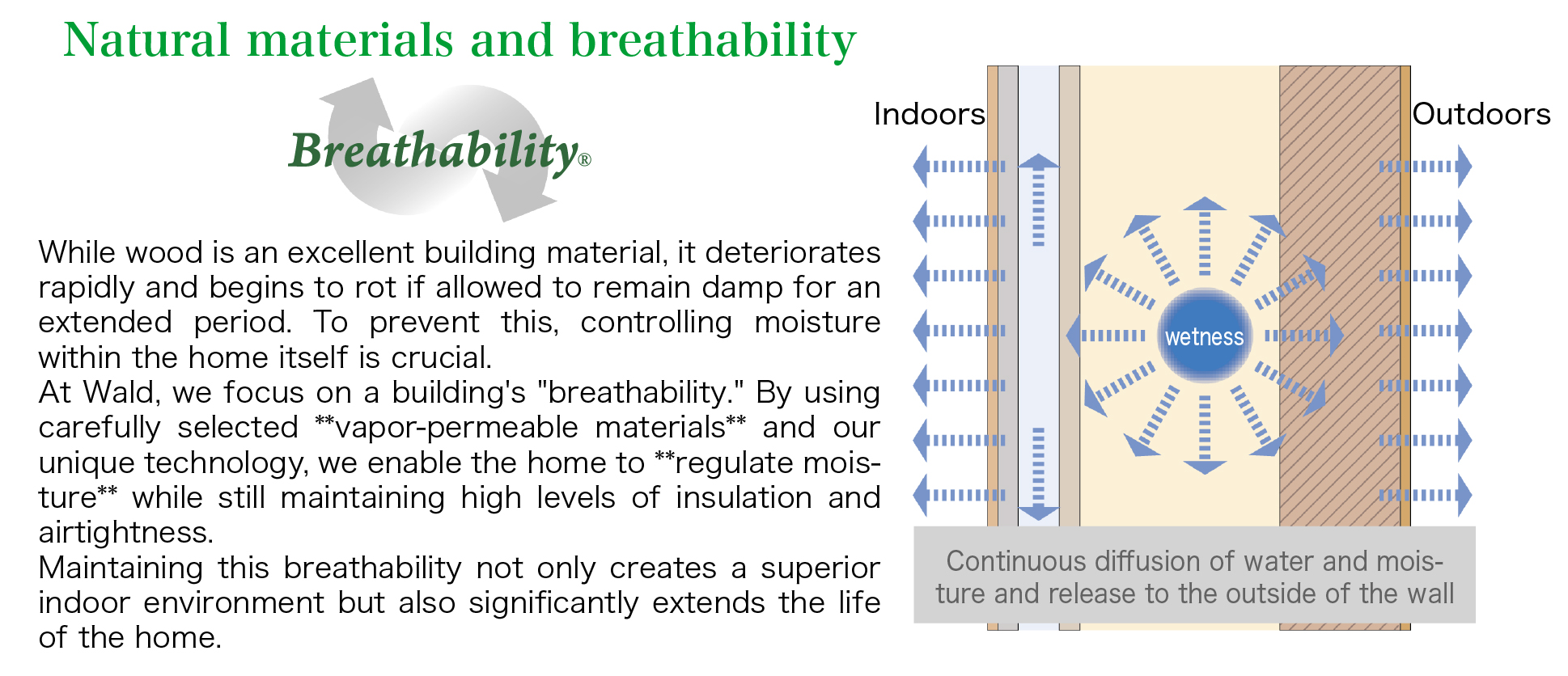

In Volume 1, I introduced our philosophy of the “Breathing Home.” In Volume 2, I explained how we use German “DAKO” windows to prevent condensation at the home’s most significant weak point.

This time, I want to focus on the area that handles the majority of a home’s insulation performance: the inside of the walls, specifically, the “insulation material.”

The “Trapping” Philosophy and Its Flaw

In conventional Japanese home building, “mineral fiber” insulation, such as fiberglass or rock wool, has been widely used. These materials are inexpensive and have high insulation values, but they share one major weakness: they are extremely vulnerable to water, especially moisture vapor.

Once fiberglass gets damp, it soaks up water and its insulation performance drops significantly. Therefore, at construction sites, workers meticulously apply the “vapor barrier” (polyethylene film) I mentioned in Volume 1, adopting a “containment” strategy to “keep all moisture out of the wall.”

However, as I’ve already discussed, this “trapping” philosophy is what increases the risk of interstitial condensation. No matter how perfectly it seems to be installed, tiny gaps around electrical outlets, plumbing penetrations, or settling over time will allow moisture to infiltrate the wall. Once inside, this moisture is blocked by the vapor barrier, finds no escape, and begins to soak the insulation, breed mold, and rot the structural columns.

Our “Breathing Wall” Solution: PAVATEX

To solve this fundamental problem, we at Wald take a completely different approach.

Our philosophy is based on the premise that “moisture will inevitably enter the wall,” and therefore, we must “design a system that safely manages this moisture and allows it to escape to the outside.”

The core material that makes this “Breathing Wall” possible is our standard-specified wood fiber insulation: “PAVATEX.”

PAVATEX, as the name suggests, is an insulation material made from “wood.” It is produced by steaming and refining forest-thinned timber into fibers, which are then compressed at high density into boards. Born in Switzerland, this insulation has evolved within Europe’s strict environmental standards.

The Three “Breathing Capabilities” of Wood Fiber

Why do we insist on wood fiber? It’s because it possesses “three breathing capabilities” derived from wood that other insulation materials lack.

- Superior Humidity Buffering (Hygroscopicity)

The core of Dr. Padfield’s theory, which I introduced in Volume 1, was “humidity buffering capacity.” Wood fiber is a material that excels in precisely this ability. The wood fibers are porous; they “absorb” moisture when the humidity is high and “release” it when the air is dry. This action works to constantly stabilize the relative humidity (RH) within the wall assembly, maintaining an environment where condensation is unlikely to occur (below 70% RH). - The Ability to Disperse Liquid Water (Capillarity)

This is the true value of wood fiber and the decisive difference from fiberglass. In the event that condensation does occur, or rainwater finds its way in, wood fiber uses “capillary action” to instantly wick up that liquid water and disperse it throughout the fibers. The water doesn’t pool in one place; it spreads over the vast surface area of the fibers, allowing it to dry (evaporate) quickly.

Fiberglass, lacking this capillary action, allows liquid water to succumb to gravity, where it pools at the bottom of the wall, causing serious rot in the foundation sill plates. - High Thermal Mass (Summer Comfort)

Wood fiber is very dense—over seven times denser than fiberglass—and is characterized by its very high “thermal mass” (the ability to store heat).

With conventional insulation, the intense heat from the strong summer sun passes through the wall almost immediately, causing the room to heat up and stay hot even at night. However, the high thermal mass of wood fiber allows it to slowly absorb the daytime heat, delaying its arrival on the indoor side (we call this time difference the “phase shift” or “time lag”). By the time the heat is ready to pass through, night has fallen, and the outside air is cooler, allowing for a comfortable indoor environment that doesn’t rely excessively on air conditioning.

[Image showing a graph of heat lag (time lag) effect]

PAVATEX (wood fiber) is not just an “insulation material” that blocks heat.

It is the very heart of the “Breathing Home,” actively working within your walls to control humidity, provide resilience against water, and even create comfort in the summer.

Coming Next

In the next column (Vol. 5), I will discuss what kind of “heating and cooling system” we choose to use within the high-performance “shell” we have built.